The title of this essay is eloquent because it shows theatre as an ongoing process. A crossroads represents a mode of movement and a condition of a journey, reminding us of a sense of theatre dynamism. I consider it important to trace history as a theatre oriented person, especially as a playwright, researcher and teacher of the subject. Here, I would only review the crucial mode of Nepali theatre to examine the nature of the ‘crossroad’ today.

In this short review, I would like to allude to that history which was very crucial for the promotion of theatre. Modern Nepali theatre has already spanned some important modes of transformations and exposures. It is very important to review at least some of those changes that occurred in Nepali modern theatre.

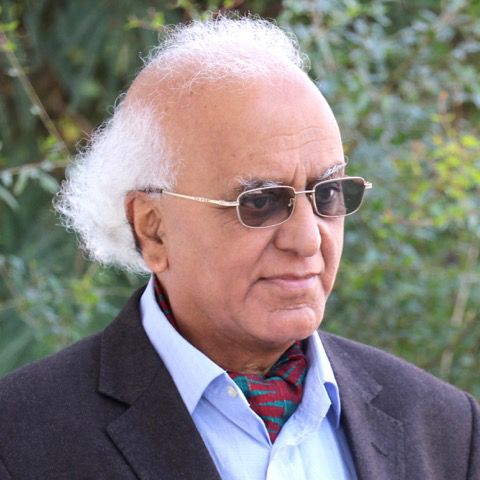

We became a member of the International Theatre Institute (ITI) UNESCO in 2000. As the founding president of the society working with other members of the cohort, I directly encountered the theatre institutions of several countries, including those of this part of the world. The Gurukul Theatre came into existence at that very crucial time. Gurukul, throughout its lifetime from 6 February 2003 to 14 January 2012, remained the most articulate and creative centre and a monitoring system of theatrical events in this country. Poetry, semiotics, symbols, dialogues of familiar kinds, and satirical and humorous utterances create the theatre’s monitoring system. Gurukul did stage all those features of the eloquent times. So much happened during this period: People lost lives, political parties holding extremely different views came together and made peace deals in 2006, and the old institution of monarchy was abolished in 2007.

Gurukul’s performances, in a subtle way, monitored these dynamics and other important modes of that time. To do so, it did not become anybody’s propaganda centre—it functioned as a free theatre space for performance. The repertory theatre grew stronger day by day. Several national, regional international theatre festivals happened during that time. Theatres that came after Gurukul continued with this culture. Several theatre artists of that period and those who came afterwards gave new directions to theatre by organising groups and creating forms.

We thought we should introduce Nepali heritage, theatre and theatre activities of contemporary times. I was thus asked to write an analytical history of Nepali theatre. I wrote a book titled Nepali Theatre As I See It, which was published by Gurukul in 2007. The book’s purpose was to familiarise inner and outer lovers of Nepali theatre with the grand cultural and realistic theatre traditions of this land and its present turns. Free theatre became a norm. Some of them even followed the model of Augusto Boal, the creator of the ‘theatre of the oppressed’.

The Covid-19 pandemic seriously jeopardised theatre activities everywhere, and Nepal was no exception. That it was a very serious period for Nepali theatre needs no elaboration here. But Nepali theatre slowly rose like a phoenix. That is a matter of great delight and hope for all theatre-savvy people. We should look from this point onwards to see how the Nepali theatre has come to a crossroads again. Without elaborating on this subject for want of space, I would like to mention the diverse features of Nepali theatre at a crossroads today.

First, modern Nepali theatre has developed a culture of pluralism. This means that no single effort and its success or failure affects the entire theatre “karma” today. Failures and successes have become the names of experiments. Second, a very significant crop of the current theatre managers and organisers had largely their origin with Gurukul. After its dissolution in 2012, the theatre artists and youths who had played important roles there started their own theatres. Some of them are playing proactive roles as artists, managers and directors in several theatres today. Others carried their legacy and apprenticeship of Sarwanam Theatre.

Third, artists and directors who were not part of Gurukul or Sarwanam emerged as organisers, managers and artists. Maithil theatre, which made a strong presence in Kathmandu with Gurukul as its venue, has been active locally. The theatre of the oppressed or the open itinerant theatres have become active again. Many theatre groups have become active in different parts of the country. Fourth, modern theatre has become an interart phenomenon. Theatre and cinema arts have created quite comfortable contact zones in contemporary times. The legacy of the first awakening of the beginning of the twenty-first century of interart relationships has found continuity and even promotion today.

Fifth, an entrepreneurial aspect of theatre has become a new feature today. Management of funds, making agreements with donors, taking land on lease and doing deals has become the character of theatre today. This had started with Gurukul, which had to roll up the carpets and pull down theatre structures as in wartime when the lease ran out. I was present on these occasions. But today, the deals are made more carefully. Sixth, the culture of theatre-going is increasing today. The emergence of young audiences is a heartening matter for theatre.

Seventh, theatres themselves are managing theatre pedagogy because academic institutions or universities do not give this subject priority, unfortunately. Finally, today’s theatres organise national and international theatre festivals. Mandala Theatre Festival is an example.

I wish to end this essay by stressing the following: To understand where Nepali theatre has arrived today, we must understand how Gurukul, Sarwanam and regional theatres created a culture of theatre. This is something that is not done by the Nepal Academy, Sanskritik Sansthan and others. Nepali theatre today is at an important crossroads, which means that the challenges and successes of theatre are affected by the broader cultural policy of the country. But the secret of the continuum of Nepali theatre is the energy and proactive zeal of the theatre people today.